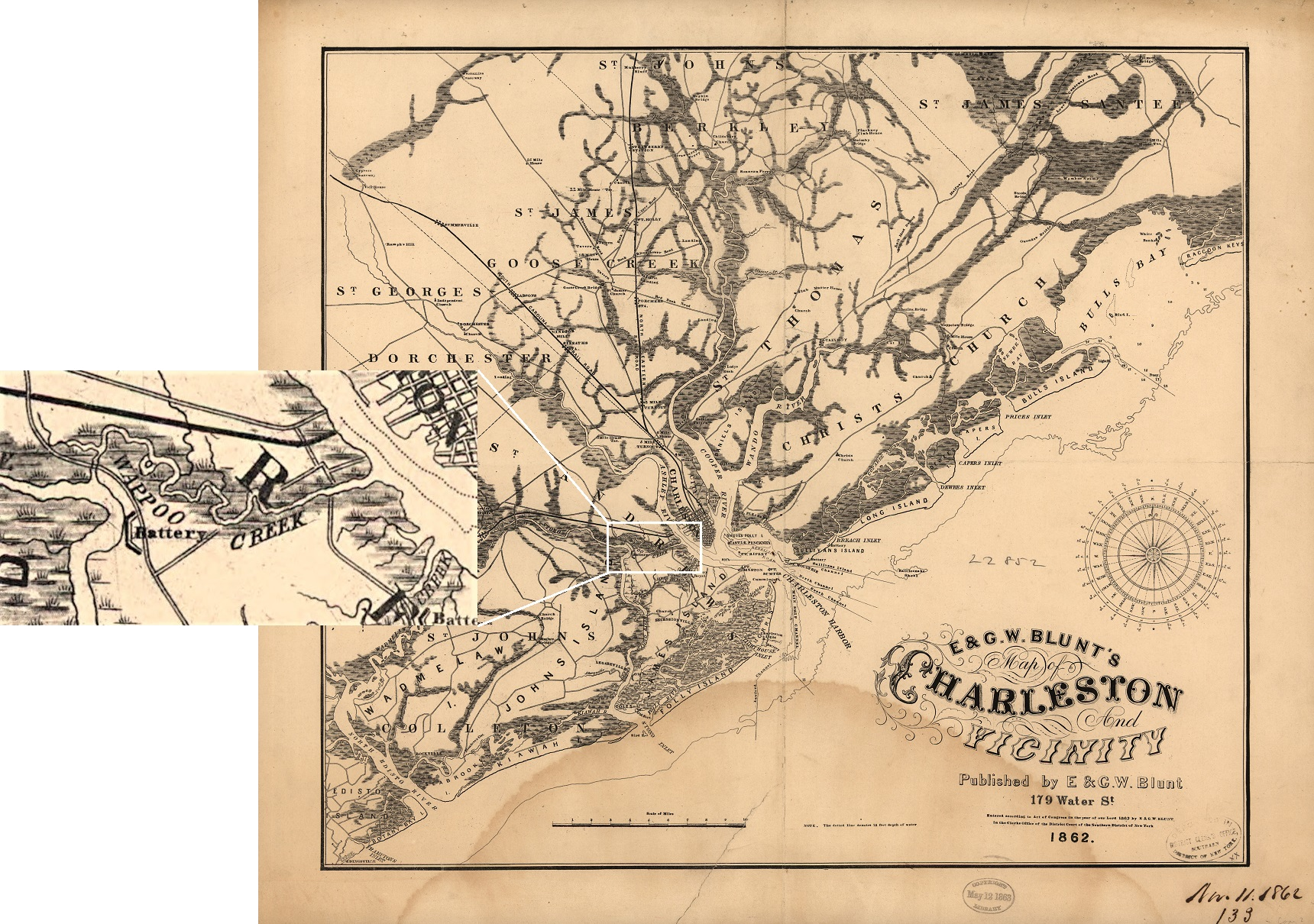

The residents of Riverland Terrace and Edgewater Park who live on either side of Elliot's Cut, which connects Wappoo Creek with the Stono River, are as accustomed to the buzz of a motorboat engine or the sight of a large pleasure yacht under full sail as are those who live next to Savannah Highway accustomed to the sights and sounds of wheeled vehicles of every type. At any time one might see coming through the cut a row of fifty foot barges piled high with timber on its way to the IP paper plant in Savannah, or an even larger chain of barges supporting a maze of cranes, pipes, and various superstructures headed to the sight of some dredging operation. On certain days the cut is frequented by tour boats swarming with tourists and sightseers or dirty looking shrimp boats strewn with nets, poles and rigging. On a pleasant Sunday afternoon anyone can usually count half a dozen pleasure craft within the space of a half hour, and if the season's right, there's bound to be some water skiers. Sometimes a canoe or a sailboat or rowing crew might even pass through the cut.

One of the first things a boater notices on passing through Elliot's Cut is how remarkably straight the waterway is. And, of course, there's a reason for this. Elliot's Cut is one of a series of man-made waterways along the coast of South Carolina, which with the natural waterways they connect, form what is called the Intracoastal Waterway. This waterway system provides an entirely inland route for water vehicles traveling north and south anywhere between Hampton Roads and Florida Bay. Today, the ICW is not only a boon to boating tourists, but a vital asset to commerce.

Elliot's Cut is an important link in the ICW. Its history and modern problems, though not exactly typical of the rest of the waterway, do provide a key to understanding the importance of the boating industry and water transportation in America today.

The first settlers of South Carolina made their livings as planters, and one of their greatest problems was getting their crops to market. To bring crops by land to Charleston, the main seaport servicing the coast for many miles around, was next to impossible. Because of the geography of the area, one could not travel more than a couple of miles without having to cross a creek or marsh of some size, and the technology of the period did not allow the planters to build all the bridges that we have today. Since overland transportation was ruled out it was necessary to bring produce to market by water.

Still, the natural waterways presented a problem, because they were inevitably long and meandering or too shallow to be navigable, forcing the planters to send their flimsy plantation barges across the open sea. Help was sought in the colonial legislature, but little more was done than to set up commissions which were in turn empowered to appoint committees who were assigned the tasks of building some particular road, clearing out some creek or the like. These committees were the overseers for the actual projects: it was the custom that the men and funds to undertake the various projects were supplied directly by the planters and and other colonists who would benefit by them.

The first legislation in South Carolina which called for the digging Elliot's Cut was an act passed in 1712 in the colonial legislature bearing the somewhat cumbersome title, "An Act to impower the several Commissioners of High Roads, Private Paths, Bridges, Creeks, Causeys, and cleansing of the Water Passages in South Carolina, to alter and lay out the same for the more direct and better Convenience of the Inhabitants thereof." As the case was, however, the title of the act was almost as specific as the act itself and was only the subject of continual debating and redrafting; and though several bills were passed over the next half century explaining the original act, no action was taken on the specific provision (calling for the digging of what is now Elliot's Cut.)

The portion of the Act of 1712 which dealt with the cutting of a passage from Wappoo Creek to Stono River was as follows : "The head of Wappoo Creek going into the Stono, be cut and made sufficiently wide, or that a new creek more convenient be cut from the head of Wappoo into the Stono at the discretion of the commissioners..." The act went on to specify that "the creek... shall be made ten feet wide and six deep..." and that it was to be dug "at the usual charge and labor of all male persons... living from New cut to the head of Stono River to the plantation of Colonel Robert Gibbes...." The carrying out of this portion of the act of 1712 would have entailed the drafting of almost all the male residents, slaves included, of James Island, John's Island, Wadmalaw Island and the West Ashley mainland district, excepting only those residents already employed in the digging of another creek.

The actual construction of the cut was quite a bit more difficult than the act implied. The colonists made use of an effect known as "sluicing," whereby once a new waterway was cut which provided a shorter route to the ocean for tidal water flow, the tides would pass through this outlet much faster than through the natural outlet, and by the process of erosion cause the newly cut waterway to become eventually as wide as the old one. This is the reason that the act only specified a creek ten feet wide and six feet deep-- today the cut is several hundred feet wide and from 12 to 18 feet deep.

But even with all the help nature would have given, the digging of the cut was an almost insurmountable task. To be of any value, the cut would have to make the natural route from Stono river to Charleston harbor substantially shorter; and near its head, Wappoo Creek makes several large loops and turns, so this was the obvious portion to bypass via a new waterway. The best site was at the base of a hill, requiring a straight section of cut almost a half mile long. A half mile is a pretty long way digging by hand, even if it's only a ditch ten feet wide and six feet deep.

Attempts were made, unsuccessfully, to complete the digging of the cut prior to 1881, when federal aid was sought to complete the project. The committee appointed to oversee the task consisted of the following men: Colonel John Fenwick, John Godfrey, Captain Thomas Elliot (after whom the the cut was named), John Williamson and John Stanyarne.

Even though the cut was not completed until the 1880's when the rice industry, the success of which was one of the main reasons the cut was needed, was in its final stages of decline, the main transportation lines were still the waterways. But the shift has been toward overland transportation in recent years, with the advent of automobiles, modern bridge construction techniques, an the expansion of residential areas into places where plantations formerly stood.

An interesting comparison can be made between commercial and recreational, large scale and private, and local and long distance uses of local roads and waterways now and a hundred years ago. Today, most overland transportation is done by residents of suburban areas commuting to and from work. Use of the waterways is more or less restricted to recreation or commerce. Local commercial use of the waterways is no where nearly as great as it was 100 years ago-- the fishing industry takes up the major portion of this category. However, the use of the inland waterway in the transport of goods to different parts of the country is much greater than it was 100 years ago. Also, recreational employment of waterways has increased tremendously during this period.

Two trends along these lines unaccompanied by appropriate changes in legislation have given rise to a somewhat heated controversy as to which mode of transportation-- land or water-- should have the right of way when such a question arises. The case in point is the late debate between pleasure boaters passing through the drawbridge over Wappoo Creek at all hours of the day and commuters who line traffic up on either side of the bridge every morning and evening. The logical solution, it would seem, is to close the bridge to pleasure boats during the peak traffic hours, but traditionally, the water traffic has always had the right of way. This is because before the bridge was even constructed, the major mode of transportation was by boat. Right of way was never a problem, for almost all overland vehicles made use of ferries to get from place to place. When bridges came into existence, no one thought to close them to water traffic in order to allow cars to pass, because there were more boats than cars. The two trends which gradually put the situation into a different light were first, the change in the employment of the water vehicle from an item of business to one of recreation and second, the growing use of the automobile as a means of commuter transportation. Together these two trends spell the replacement of the boat by the car as the standard household vehicle.

The laws regulating traffic flow over and under bridges have been slow to catch up with these trends. The visual effects of this lag are terrific traffic jams on mornings when the bridges open to let some yacht whose top mast just fails to clear by a couple of inches and once the bridge is open gets stuck in the open position. Several such occasions have backed up the traffic on James Island in front of the Wappoo Creek bridge for several hours and several miles. It is no wonder the Island people were so fed up with the old bridge (which got stuck rather often, I have heard) and finally got a new one in 1955 at the cost of almost a million dollars. It's no wonder that even now they want their own bridge across the Ashley River!

Well, it seems our forefathers, in a rather indirect way, have left us a sort of transportation problem. Another problem which has been bequeathed us, though it is by no means as controversial or as much a problem, is the continuing erosion of the banks of Elliot's Cut. The reason I mention this is that my family live on a waterfront lot which when purchased was held intact in one part by a large tree trunk and along the rest of the waterfront by a quantity of old building material salvaged from some war barracks no longer needed and dumped rather precariously along the bank of the cut to lessen the effects of erosion. Since the lot was purchased the tree trunk has died and is slowly being washed away, and our land has begun to wash away with it. The concrete blocks along the rest of the bank have also proved inadequate, and now the erosion is being corrected by using these blocks to build a seawall.

It is left to each individual landowner to care for his own waterfront. Most have constructed some sort of wall, but there are some stretches of bank which are unprotected, either because they are municipally owned or because their owners don't bother to do anything about the problem. While passing though the cut, it is interesting to notice all the different sea barriers the residents have constructed along the banks. Various types of sea-walls include concrete facing, walls of piling and timber, cinder-block walls, clay brick and concrete blocks. Some of these schemes, even the concrete facing, have proved inadequate and have had to be replaced.

Both the problem of priority in transportation lines and erosion along the banks of the cut have arisen, either directly or coincidentally, from the methods and way of life of the early South Carolina planters. Changes in transportation and technology give testimony to the fact that new ideas and developments are all too often incompatible with old customs and traditions.